The content of this website is ours alone and does not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Government, the Peace Corps, or the Eswatini Government.

Umkhombe (White Rhino) at Hlane Royal National Park by Tamera

The white rhino (Ceratotherium simum) is not white at all – it’s a mis-translation of the Afrikaans name, wyd renoster, with the wyd meaning wide for its square bottom lip. Take a look:

Swazis also have a different name for black rhinos – bhejane. In scientific nomenclature, it’s not even in the same genus as the white rhino – it’s Diceros bicornis. (This photo is from https://www.wwf.org.uk/learn/fascinating-facts/black-rhino since we didn’t see black rhinos at Hlane).

The horns from all five rhino species (the other three are in Asia) have been banned from global trade since 1977 under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), although the Southern White Rhino is doing the best for population size – 15,942 individuals vs. 6,195 black rhinos (https://www.savetherhino.org). This is primarily because of game ranching in South Africa. But didn’t we hear that the last white rhino male died in Kenya in 2018? Yes, but that was the last male northern white rhino.

This ban on selling rhino horns primarily for traditional medicine in China and Vietnam is quite controversial. Proponents of lifting the ban (including Eswatini who actually presented the proposal to lift it to CITES) say that the game ranches and game parks could sell rhino horns and fund conservation much better since rhino horns typically sell for $15,000 to 30,000 per pound (Cheung et al. 2021, Frontiers in Ecology & Evolution). The proponents say the horns could be micro-chipped to make sure they’re not from animals that were poached. They also think that having a legal trade could help control poaching. Those who want to see the ban in place think that the market for the horns is unknown if one or a few countries were allowed to trade the horn and so we shouldn’t risk lifting it. CITES has voted to keep the ban in place. Poaching of rhinos used to be worst in East Africa, but now the worst is in South Africa with > 500 animals killed per year (down from a high of 1,549 in 2015 according to www.savetherhino.org).

White rhinos are huge, weighing in at 5000 to 6000 pounds! They are 5-6 feet tall at the shoulder and 10-16 feet long! You can imagine that wide bottom lip mowing down the grass as they graze along. They seem to be pretty social animals – we saw about a dozen of them right outside of the car. And they’re fast for such a bulky animal! (No sound on this one since I had the car running.)

Red-billed oxpeckers groom ectoparasites from rhinos just like they do from many large mammals in Africa.

It was a hot day at Hlane so they were wallowing in the mud. Sound on for this one!

Did I say that rhinos can move quickly? I moved a little more quickly when one rhino was a little disturbed when we were driving by. (Disclaimer: No Peace Corps Response Volunteers were hurt in the filming of this video).

Hope you enjoyed the videos, I had to learn a bit to do it!

Ready for Tilwane (Animals)? by Tamera

Last Friday, we went to Mbuluzi Game Reserve for Rich’s work! We delivered coffee from the farm, and Rich met with the Reserve Manager. We met in the field so got to see some of their work on brush clearing – a problem throughout the world in arid and semi-arid ecosystems. First we had to drive to get to that side of the reserve, with a little river crossing – much easier than the one I did in Kakadu N.P. in Australia with my mom and sister.

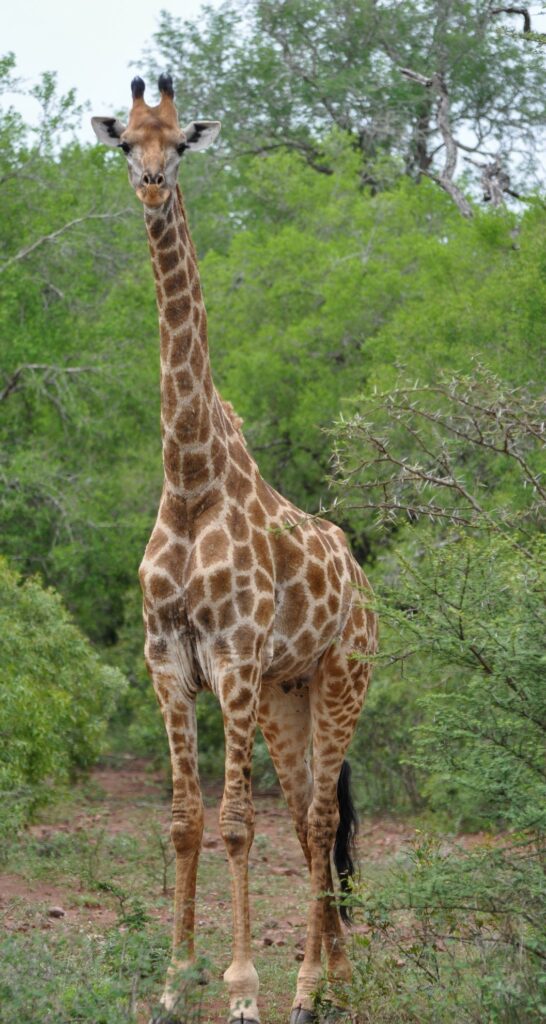

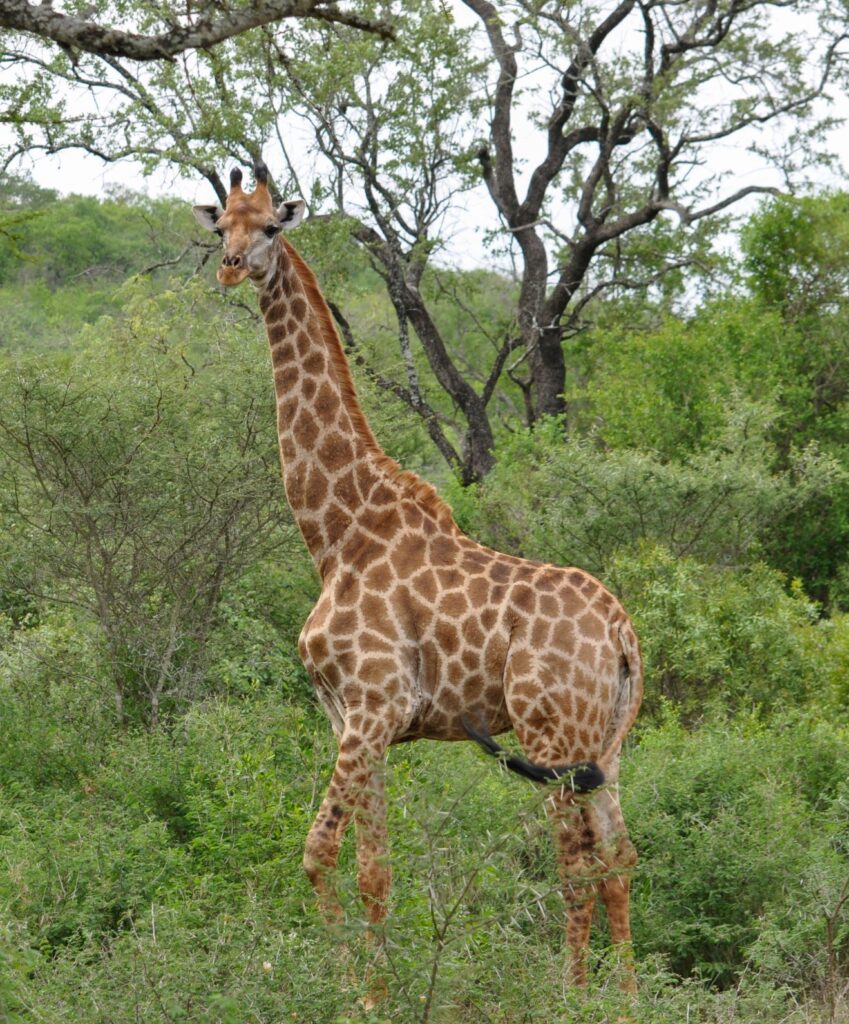

We also got to see giraffes (tindlulamitsi)! I just love giraffes (who doesn’t) and was excited that they are present here since I have been pining to see giraffes. In Tanzania, I couldn’t wait to see an elephant, but for some reason, this time it was giraffes.

After I bought a car on Saturday (Peace Corps doesn’t allow volunteers to drive, but I’m not a volunteer, just Rich) – a 2006 Nissan xtrail with 4WD – we headed to Mlilwane Wildlife Sanctuary. This is the oldest conservation area in Eswatini. They do some breeding of some of the antelope so they are mostly in large fenced areas, but some of the more common animals, you can see as you walk around. One of the nicest things about game reserves in Eswatini is that there are no big cats (Hlane is an exception), so you can walk or mountain bike in most of the parks. I got in 17,000 steps on Saturday.

These majestic guys are male nyala, followed by a female and then a baby nyala. Aren’t the baggy shorts on the males and the face-paint on the baby fun? The difference between the males and females in color and size is striking – that’s called sexual dimorphism.

There was a massive female warthog with her cute babies – baby mammals are always cute, aren’t they?

Nice views of zebras along our walk. They always seem fat and happy.

Southern Africa seems to have many more species of antelope than East Africa. I’m not sure why – it may be that there are more habitat types, particularly of forest and woodland. These are blesbok (an Afrikaans name, “bles” being the word for a blaze that you might see on the face of a horse).

Then springbok, impala and two photos of waterbuck (Rich says they look like they’ve sat on a newly painted toilet seat).

These are roan antelope. These were probably some of the animals in the breeding program. The second shot shows the male tapping at the back of a female. They didn’t mate. Note he has tubes over his horns. Not sure if that’s to protect the females or other males.

Lots of great birds. This first one, the white-fronted bee-eater was really common. On our hike, we found that they nest in the sides of cliffs, just boring a hole into the dirt.

Here is a village weaver. Notice the difference between its nest and the thick-billed weaver’s nest which I posted about earlier. The nest dangles from a tree branch rather than being built on two cattails. I think the tree with all its nests and birds looks like an African version of a Christmas tree.

This is a hamerkop which has a head that has been likened to a hammer. It is a monotypic family (that is, this is the only species in it) and found only in Africa and Madagascar.

These Southern Red Bishops are closely related to the weavers. Isn’t the red amazing?

The first time we saw these ground hornbills in Tanzania, we thought Gary Larson should have made a Far Side cartoon about them posing as cowboys.

These Blue Cranes were doing mating dances, but unlike our sandhill cranes, they were running all over the place, and then would come back together to dance.

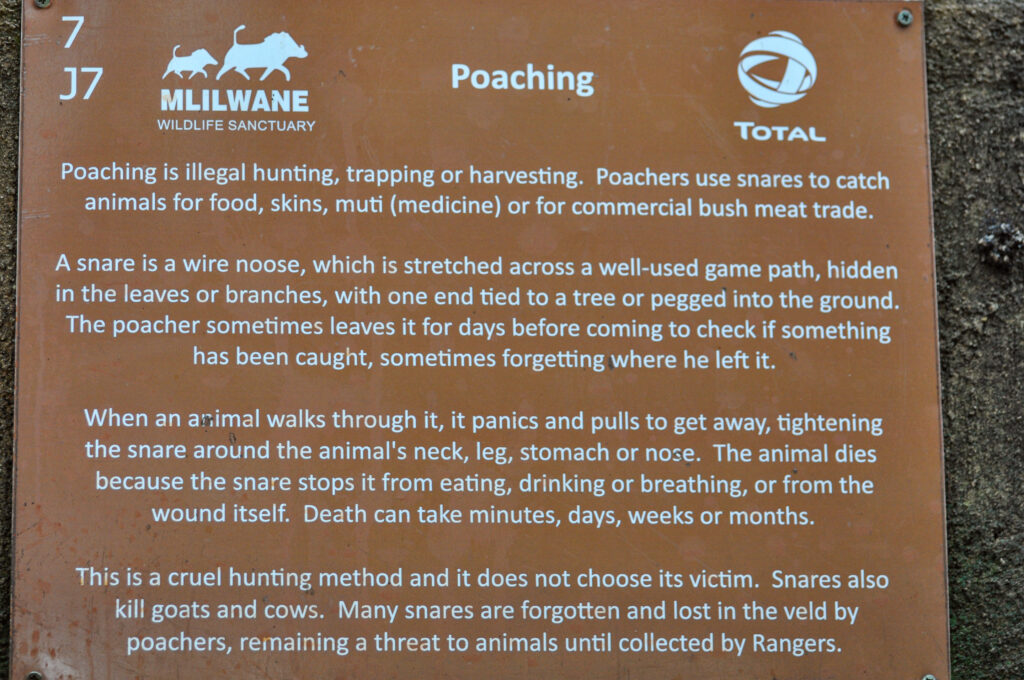

At the lodge, there was a display about poaching with snares. Rich remembers the rangers gathering snares like this at Mwalula Nature Reserve when he worked there as an ecologist with Peace Corps back in the 1980s.

On Sunday, we climbed Execution Rock (Nyonane Peak), where stories say that local people suspected of witchcraft or criminal activity were forced to walk off the cliff at the point of a spear (www.thekingdomofeswatini.com). It was a lovely view of the valley. And here’s Rich, going up a ladder to cross a fence.

And we did see a crocodile – don’t worry, it was when we were driving out, from the car!

Thick-billed weavers (Amblyospiza albifrons) by Tamera

Weavers are small songbirds and can be identified by their nest since each species weaves a distinctive nest. Thick-billed weavers have a large bill. The male weaves the nest and may have as many as 8 nests going at once. The female does most of the feeding. In this picture, you can see the male is mostly dark (many weavers are yellow so this dark coloring is distinctive). You can also see a patch of white on the wing and on the forehead.

These thick-billed weavers generally build their nests in wetlands with two reeds holding up the sides of the nest. Many weavers, by contrast, hang their nests from tree branches. In this case, these plants are cattails, called Typha capensis, a species native to southern Africa.

After the eggs are laid, the birds make the nest more secure by weaving a tube for the entrance.

Here is a nest just being started. You can see by the color of the grass that it’s pretty fresh.

Here are a couple photos of the male weaver doing the weaving. Interesting that the bird is dexterous enough to do this with that thick bill!

And here’s a bonus photo of a damselfly, just because.

What are we doing here? by Tamera

We’re here on the Lebombo Plateau in Eswatini. Richard is a Peace Corps Response Volunteer. He’s helping to further the establishment of Muti Muti Conservancy. I have just joined him, and did I mention there’s swimming pool here at the farm? (My previous blogs from my Fulbright experience in Tanzania in 2019-2020 are still posted here as well).

A Coffee-Infused Cultural Experience

Many towns, small and large, in Tanzania have cultural tourism opportunities. You often show up at the village centre and you can be set up with a guide to take you through the market or to visit a natural area or to visit a home and have lunch. There are often signs in the village giving you a number to call (“kupiga simu” in KiSwahili which means to hit your phone (number)). This seems like a pretty cool thing all around: local people get to show off their culture and make some money, while tourists get a bit of a taste for how some people live in the country that they’re traveling in. The small village where we often go to the farmers’ market to buy vegetables, Tengeru, has their own programme.

A few weeks ago, Rich and I traveled to Moshi, which is the jumping off point for climbing Kili. I actually booked a room to stay in over AirBNB for $20. The next morning we drove up to Materuni Village. Most tourists, of course, are driven there by their safari company, but we got to go up in tvhe RAV4. Almost immediately, a guy riding on a pikipiki (motorcycle for transport, often has 2 passengers and “stuff” as well as the driver) stopped us to ask if we were going to the village and if he could be our guide. It was good that he “called” us since we a couple of different young men ran next to our car to see if they could be our guide. We said, no, we’d already arranged it with “Mercury.”

When we arrived at the village centre, Mercury showed up and we paid for a trip up to Materuni Waterfalls. Mercury was a great agricultural guide, pointing out lots of different crops and explaining how they’re grown. We saw a couple of different types of bananas – for eating or for making “wine” which we got to sample later on and then our guide even bought the two men in the group a bottle to bring home – elephant ear or taro, maize, and shade grown coffee, among others.

Some enterprising boys (too young to be guides yet) had caught a chameleon. I got to take it from Mercury and let it crawl up my arm, too.

Materuni Falls is pretty spectacular, although it was so wet that we didn’t spend a great deal of time there.

We had thought about just hiking to the falls and then leaving but decided to do the coffee tour as well. So glad we did since it was very fun and we learned some things. We also got to eat lunch with a spectacular view of the surrounding area.

Coffee has three coats that need to be removed or cracked. The first coat is the berry itself. Mercury explained to us that people used to remove the berries by hand until growers got ahold of small McKinnon mills. The company that introduced the mills required the growers to sell them all their production for five years. Now, though, the growers own the mills and much of the coffee is sold through a cooperative.

After the first removal, the beans have to be washed to remove the slimy material that remains. This is where we got to pick up the process.

This second hard coat is removed by pounding the beans in a mortar with pestle. All of these processes are done with singing and chanting, and it was quite fun.

Work!

Pole sana (very sorry, in KiSwahili) that I haven’t posted for a long time. I’ve been busy with a few things that I’ll tell you about. There have also been some transitions. I’m not very good at keeping up with other things when both of these are going on!

First, the biggest transition, of course, is that Rich is here! Wonderful to have my partner here to experience all these new things together.

As far as work goes, the past few weeks have culminated with submitting a proposal to the Bridge Collaborative with my collaborator here at Nelson Mandela. The Spark fund is designed to help teams take great ideas and bridge them to making a larger, even global, impact. This first deadline is to become one of 25 international teams (they also accept 25 US teams) to do some more training and submit another proposal in November for funding that would start in January.

My collaborator and I have pulled together a diverse team to work on Rangeland Restoration. The team is comprised of natural and social scientists, local NGOs with on-the-ground experience, and local stakeholders. It’s pretty exciting to think about what this group could do.

There were a couple of experiences leading up to this proposal. First of all, three weeks ago (the first week after Rich arrived), we got to participate in a Stakeholder Forum with the Northern Tanzania Rangelands Initiative. The first day was a field trip and the second day was a meeting.

The first day was amazing. We traveled to Longido, Tanzania, where we met with government officials and got to see some school kids first sing a song about climate change and then perform a play about resolving human/wildlife conflicts.

Then we rode in buses about 2 hours northwest of Longido to meet with a community about grazing issues. What we didn’t know, and even the organizers of the event didn’t know, was that there was going to be a huge celebration. As we got off the buses, we were met by about 200 Maasai women who were singing.

But the rangelands are in pretty bad shape. According to the United Nations, drylands comprise ~41% of the Earth’s land area and support over 2.5 billion people. Up to 20% of these lands are degraded, putting ~250 million people at risk for malnutrition.

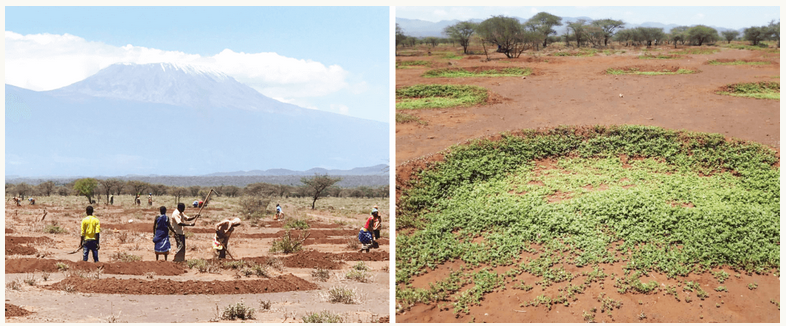

These rangelands are in the rain shadow of Mt. Meru and Mt. Kilimanjaro, and also this is a photo from the end of the dry season. The long rains failed earlier this year. As a restoration ecologist, I’m convinced that active restoration is now required to move these rangelands to be more productive and that it’s not enough to just reduce grazing levels.

Shortly after this field trip in Tanzania, Rich and I attended the World Conference on Restoration Ecology in Cape Town, South African. There was a lot of talk of the United Nations announcement of the Decade of Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030). The ideas for considering rangeland restoration and not just forest restoration are timely since we are also just moving out of the UN Fight Against Desertification (2010-2020).

I am enamored with the technique that an NGO called justdiggit.org has employed for active restoration to improve rangelands. They worked with a Maasai group in southern Kenya to determine what methods the Maasai were interested in to do rangeland restoration. The group ended up settling on digging 78,000 small berms by hand before the rainy season. Once the rains arrived, the berms captured a bit extra water and plants germinated within the berms, greening the landscape. Justdiggit is also working in Tanzania in the Dodoma area. A graduate student here at NM-AIST is now employed by justdiggit as well. I hope to see collaboration with NM-AIST, justdiggit, and some of the NGOs in the Arusha area who are very knowledgeable about conditions here to consider adopting their techniques.

My First Field Lab at Nelson Mandela

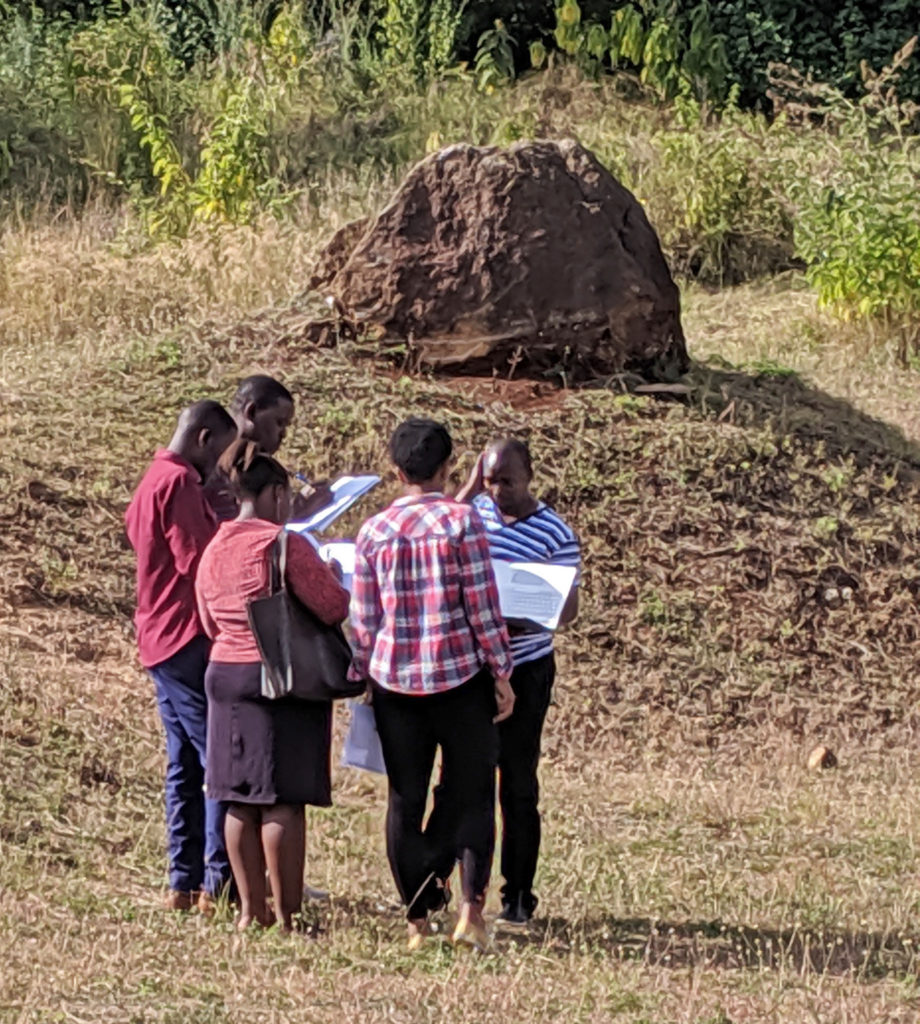

Today I taught five PhD and MSc students in the biodiversity program here at NM-AIST about qualitative monitoring for soil and site stability, hydrologic function and biotic integrity. It was my first chance to take them out in the field. We went down to the basketball court where it had been dug out and we could see some signs of erosion.

The best part of the lab was listening to them discuss each point in KiSwahili – I’m taking a class in the evenings and some of the language is starting to come back to me from my Peace Corps service in Kenya. Their discussion was primarily in KiSwahili with some English words specifically from the exercise thrown in: “Angalia erosion” (Look at the erosion).

We were finally chased out of sitting to discuss the analysis when a bee swarm that we had noticed suddenly lifted out of a tree to move to somewhere else. We also decided to take a different path home since they seemed to be hovering right above our original path.

Visiting Rau Forest Reserve in Moshi

I went to Moshi to visit my Fulbright friends on Saturday. We all met in Chicago at a pre-departure orientation. Moshi is on the slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro. While there, we got to hang out with another Fulbright family who have just finished their Fulbright stay. Sometimes it is nice to be around other Americans just because you have a lot of assumed knowledge.

It cost about $2 to get there by bus – $1 to get to the road and another $1 to get all the way to Moshi. I didn’t have a seat at first since they leave from Arusha full. I got on in Tengeru. There were a lot of stops to drop people off and pick people up. I had a book on kindle on my phone so that was okay. My legs didn’t fall asleep like they would riding the matatus in Kenya.

On Sunday we did a tour of Rau Forest Reserve on the outskirts of Moshi with Rau Eco and Cultural Tours. Linus was our guide for the trip through the forest. He was really knowledgeable and passionate about conserving the forest. He told us the story of his company while we were having some snacks – three young guys graduated from Tengeru Community Development College close to Nelson Mandela. They decided to start this business Rau Eco and Cultural Tourism Enterprise. It took a few years to just get 6 reviews on TripAdvisor. An Austrian business professor visited and spent 3 weeks with them helping to figure out a master plan for their business. She had them do some seemingly weird exercises – like walk into the forest and find a good place to meditate. They were supposed to spend 30 minutes at it and ended up spending a couple of hours!

Upon entering the Forest, it was cooler and a lovely spot to be in on a warm Tanzanian day. We saw Colobus Monkeys right away and Linus told us about their diet, behavior and conservation. He also pointed out a number of indigenous tree species, giving their common names in English and Swahili and their scientific names. He told us how each tree is used in traditional medicine. Some trees had termite tracks on the outside but were otherwise resistant and so were good for building, while others had been eaten by termites.

One of the best parts of the hike was going into the middle of the forest on a “silent walk” so that we could really hear the monkeys roaring about their territories, the birds, and even the bees buzzing around. We then had a little snack (chips made from bananas) and did another activity of meditating while experiencing the heart of the forest.

We went to what is probably the largest Mvule tree (African Teak) in existence. There were some young Tanzanian Scouts and their Scout Leader there as well.

Next we went out into the nearby rice fields and saw other birds and how Tanzanians plant other crops on the border of the rice fields. It was so green! Mr. Benjamin, a local farmer, climbed a palm tree and brought us each a fresh coconut. He hacked it open with a machete so we could drink the milk. He also cut some sugar cane so we could have some more sweetness.

One thing that I appreciated is that Linus was able to answer all kinds of questions, and was really good at judging just how much information we wanted (I wanted a lot!) Rau Ecotours have also spent countless hours picking up plastic bottles from the forest. Linus talked about local people being skeptical that they could clean it up, but their educational outreach has seemed to have a big impact.

Then it was back to the headquarters where we had lunch provided by a retired doctor and his wife. It was a nice Tanzanian end to our delightful day.

So What Am I Doing Here Anyway?

I applied for a Fulbright Fellowship to be here at the Nelson Mandela African Institution of Science and Technology last year. I decided that Tanzania would be a great place to do a Fulbright, and so I sent out emails to universities here. Prof. Anna Treydte at NM-AIST answered my email and got an invitation letter from the Vice Chancellor in just a week. This is a Teaching/Research position, but it’s a graduate school so teaching will be very different than at home. I’ll either teach workshops or classes on restoration, savanna ecology or experimental design and statistical analysis.

I also developed a research proposal to determine techniques to use to restore a savanna ecosystem after removal of the invasive tree, Prosopis julifloria. This tree is considered one of the worst invasive species in the world. It was introduced in the 1980s in Kenya, Ethiopia, South Africa, Australia, and Indonesia. Another Fulbrighter who I met in Chicago at our pre-departure orientation was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Senegal and told me that the forestry technicians planted. . . yes . . . Prosopis juliflora.

Planting grasses rather than shrubs or trees after removal of the invasive will probably lead to better outcomes. Grasses have a fibrous root system and generally take up soil water before it has a chance to percolate down to the roots of trees, making it very competitive. However, an interesting point is that replacing a tree with a grass has implications for climate change. Carbon sequestration in grasslands is most likely lower than in a savanna or woodland. So, an interesting ecological question is how much better do restoration outcomes need to be to consider using a grass instead of a native tree or shrub?

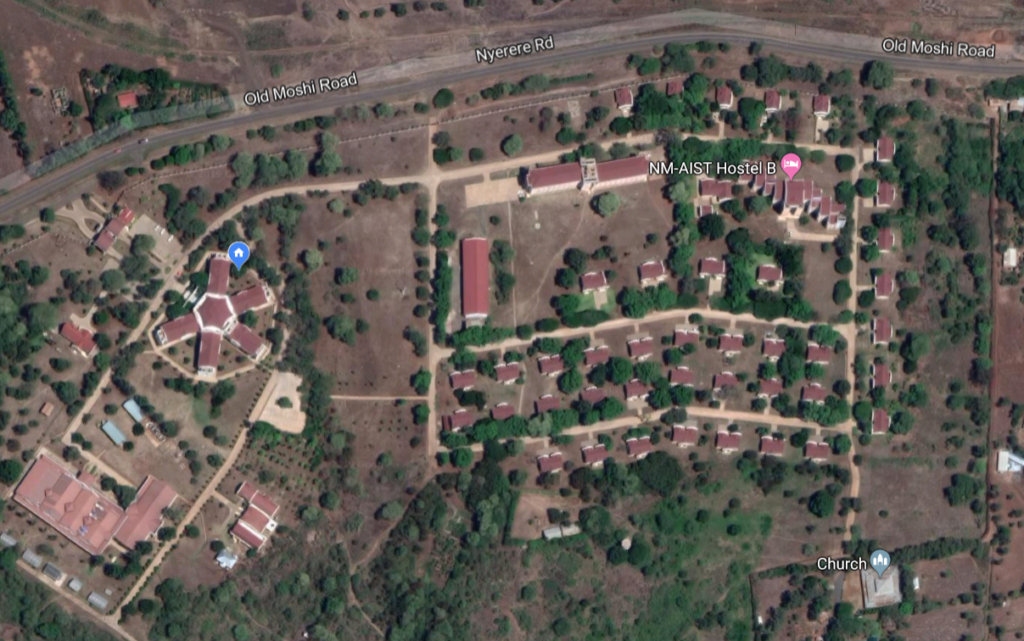

The image is of the campus. My office is in the main building with the five wings. My house is across the street from the hostel. The hostel is where the M.Sc. students stay. Ph.D. students stay in the houses as duplexes, and faculty stay in individual houses.

If you’re interested in commenting, please login with your email address. Once I approve one comment from you, you’ll be free to comment as much as you want without my approval. Sorry that I need to do this, but you know what it’s like with open comment sections.